Synopsis

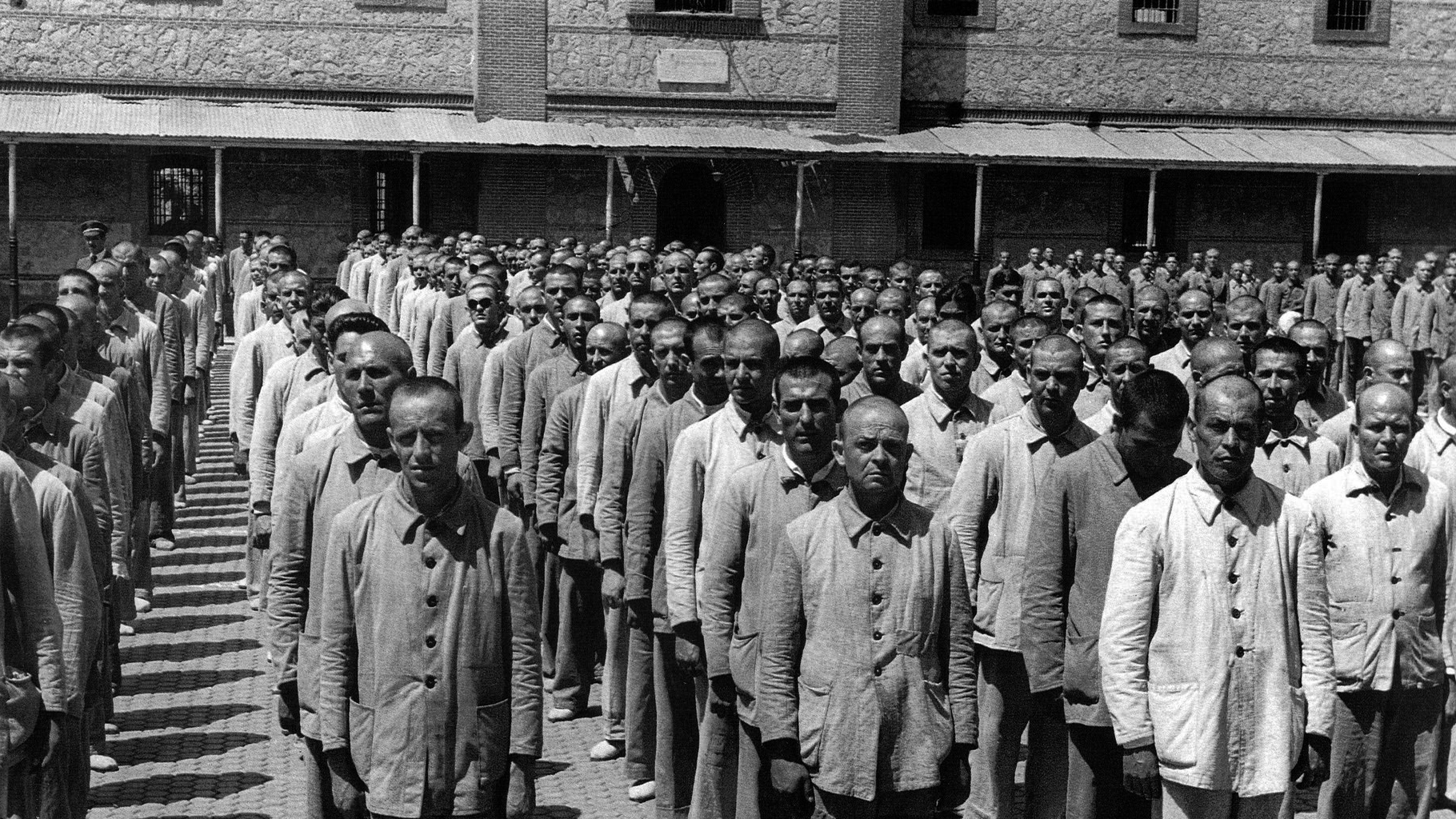

After the success of Franco´s Settlers, their first encounter with Franco’s dictatorship, filmmakers Dietmar Post and Lucía Palacios now tackle one of the most undisclosed chapters of European history: the allegedly organized extermination that took place in Spain under General Franco’s fascist dictatorship between 1936 and 1975 after he established his power with the help of Germany, Italy and Portugal. To this day no one has been prosecuted for the regime’s systematic atrocities; victims haven’t been rehabilitated. Over 100,000 people are still missing.

After a Spanish judge´s attempt to accuse Franco and his generals for crimes against humanity failed in 2010, Franco’s victims filed a complaint in Buenos Aires, known as “Querella Argentina”. Now for the first time, an Argentinian investigating judge, María Servini, has issued 24 international arrest warrants against high-ranking representatives of the Franco dictatorship. The filmmakers accompany her as she tries to initiate court proceedings against the accused, proving that a reappraisal of Spain’s darkest chapter is long overdue.

Franco on Trial debates specific crime cases presented in the Argentinean Lawsuit. By interweaving never-before-seen archival material with current footage and by delivering a historical contextualization of each case the film itself demonstrates new evidence. In one of the key scenes, the film creates a sense of the impending lawsuit’s actuality when one of the suspected perpetrators is confronted directly with the accusations by the plaintiff, the investigating judge and the plaintiff’s lawyer.

The film has been in the works for over 8 years. During that time the directors managed to gain access to people from both sides of the conflict, including the daughter of a general in the 1936 coup who still counts a silver-framed portrait and personal present of German Nazi-leader Hermann Goering among her possessions.

Franco on Trial reveals an almost forgotten part of 20th century European history and raises the question: Will the so-called “Argentinian Complaint” become a Spanish Nuremberg?

Comments on the movie

Ana Messuti

(Doctor of Law and lawyer for the victims of Francoism)

I liked the film very much: it is complete, with lots of information and images we didn’t know about before. It presents itself in a coherent form and has an extraordinary quality.

The film Franco On Trial’s greatest accomplishment is that it positions the complaint in a broader international context, pointing out Francoist Spain´s alliance with the Axis powers in Germany and in Italy. This is crucial from a legal point of view as it places crimes against humanity in an international context by crossing Spanish frontiers. In this way, the victims -specially the eternally forgotten victims of deportation and exile- are entitled to act as plaintiffs. They are all victims of the same regime, which had the help and complicity of other regimes. This makes them even more vulnerable. It is essential to highlight how Franco On Trial accomplishes this correlation since other films on the subject barely do so.

The Spanish tragedy is part of the German, French, well, the European tragedy. The Spanish Civil War is not limited to being civil nor Spanish. The international participation can be seen on both sides within the conflict. The more the conflict is internationalized, the more the crimes against the civil population are internationalized.

Kerstin Stutterheim

(Dr phil, Professor of Media and Cultural Studies at Bournemouth University, UK)

Cinematic documentaries give people a voice otherwise not heard, as Peter O’Rourke once said – but there is more. It is the tradition of poetic cinema to allow not just an argument to develop but to invite the audience as citizens, on eye level and as eye witnesses, to form their own opinion about an event, fate, topic. The traditional documentary approach which is cinematic standard primed by Vertov and Ivens, still used by international awarded filmmakers as Guzman or Mettler, enables the audience to familiarise themselves with a situation. As the audience we are allowed to get to know the people involved and their individual stories, as well as the complexity of the interaction of personal destinies and a historical situation or period. This is the quality of that aesthetic tradition which is flexible enough to be adapted for particular stories, such as the one told here. And, this form allows to unfold the particular in the general.

From my point of view, living in a time of populistic media, fake news and neo-liberal opinion making, a film such as Franco on Trail creates a good counterweight to latent and indoctrinated media productions.

In Franco on Trial the filmmakers are introducing us to a dark and not much known period of European history which influenced many parts of the world. And, it gives an idea of hidden processes involved in contemporary politics in Spain and behind.

Together with the central figures of the judge and lawyers from Argentinia, we – the audience – get to know facts and memories which are told, and actions connected to the investigation are shown and explained. Thus, we can experience the dimension for individuals as well for society. Post and Palacios are introducing us to the complex work involved in such a trial, and the importance for so many survivors and relatives of the victims as well as for the families of the perpetrators.

The exceptional quality of the film results from both sides getting a voice – those against whom the killing has been directed; and the side of the perpetrators. By enfolding the dimensions of the time and events of the Franco dictatorship slowly but steadily the pure horror of what happened there becomes more and more apparent. The judges and anthropologist involved allow us to get a bigger picture, to reflect on the events, motivation and importance of the trial – although after such a long time. It is important to get to know about the crime committed against democratic thinking people, about a calculated genocide against republicans, Jews and women who wanted to live on their own rights.

By deciding for the aesthetics of a poetic documentary the filmmakers are gently introducing us into the story. No emotionally heated up comments require us to provide an immediate response here. The filmmakers look the protagonists in the face, giving them space – and so us. We can relate to them, understand their pain or their desire to provide enlightenment. This cinematic method achieves long lasting emotional and intellectual response, thus initiating a discussion about the film and its topic.

Thus, the film is about the events there and then but at the same time it is a metaphor for genocides happening again and again all over the world.

I wish the film, the filmmaker and in particular the protagonists, all people involved in this production a broad audience and vibrant discussion.